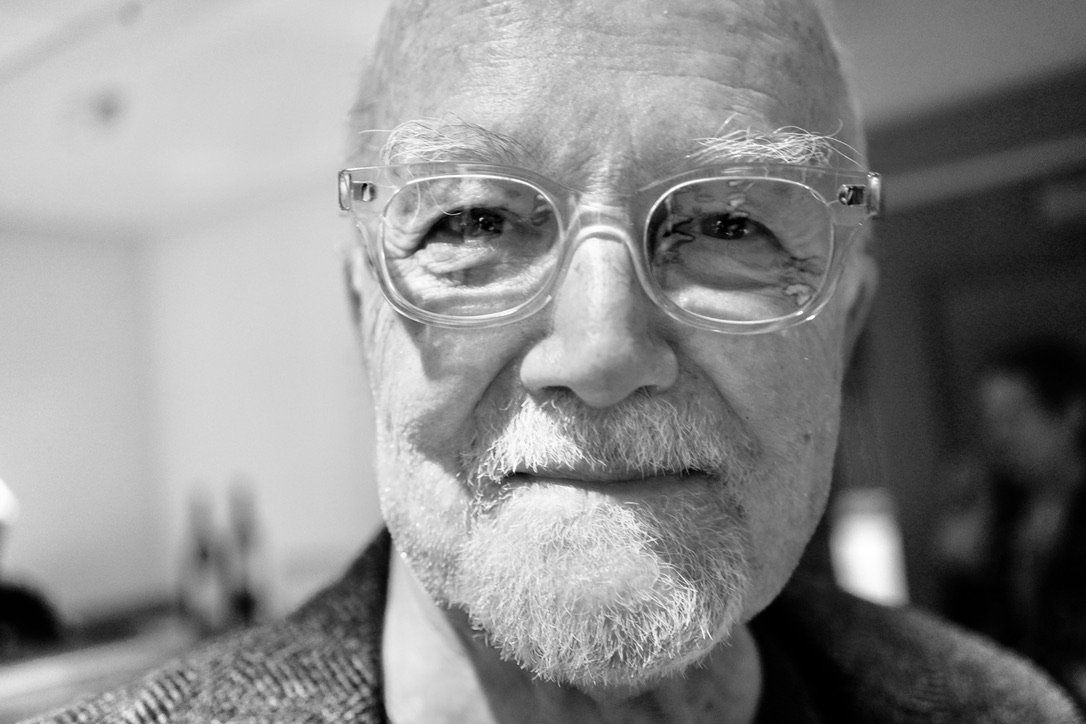

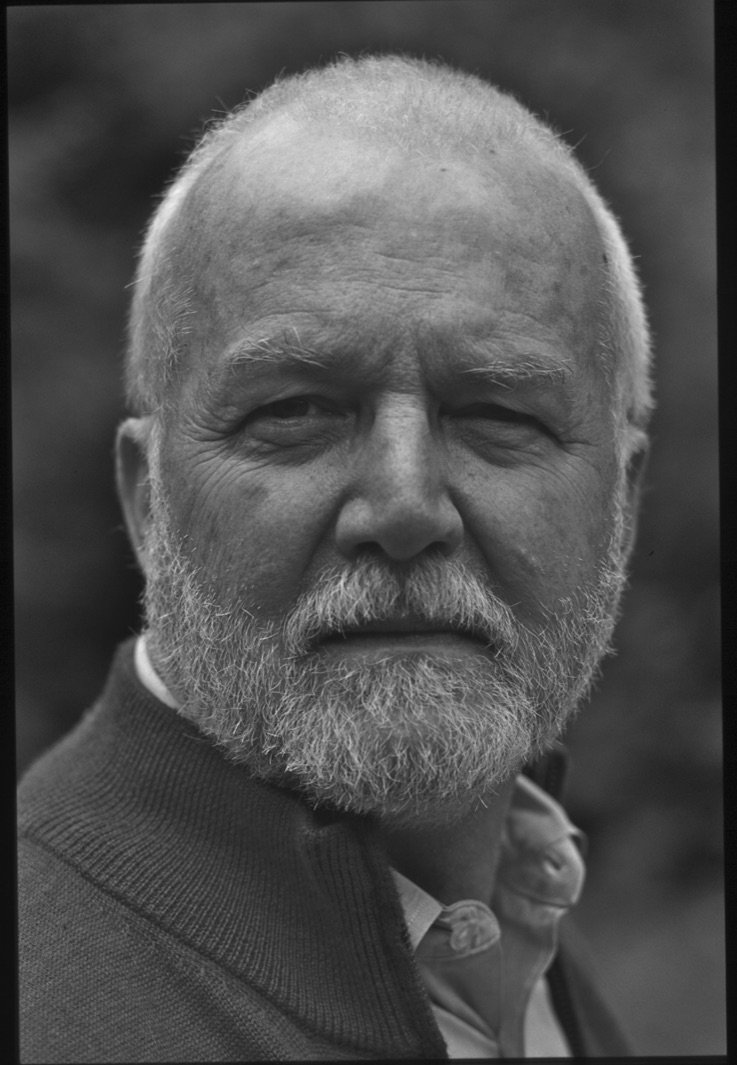

Russell Banks

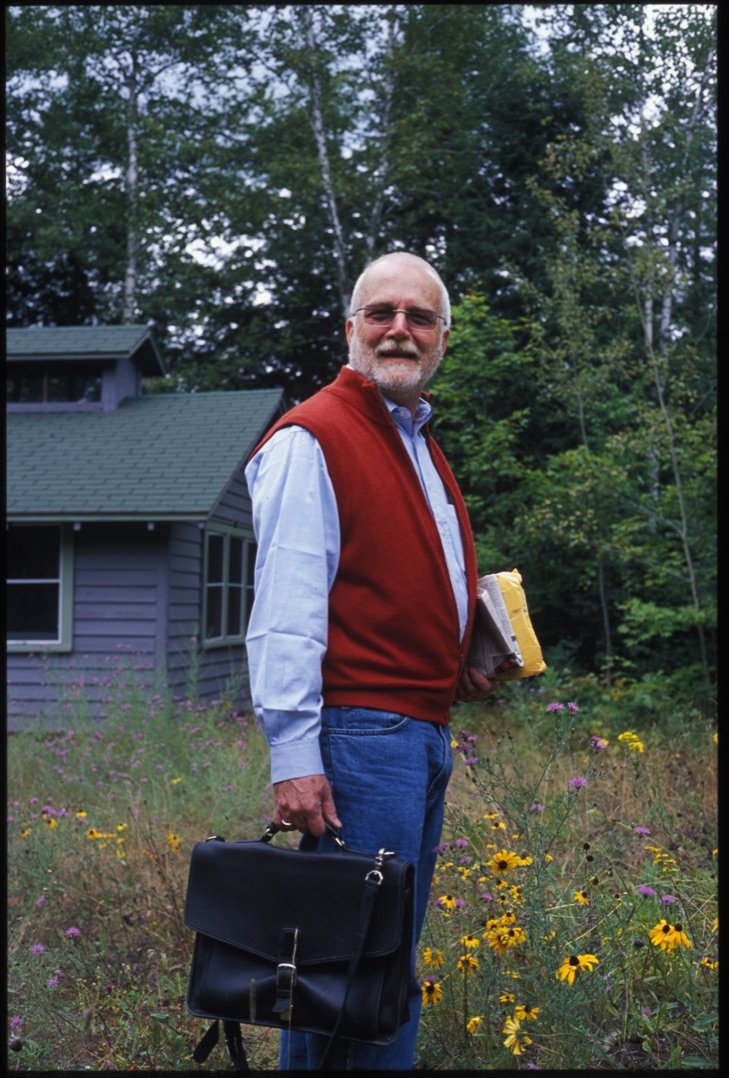

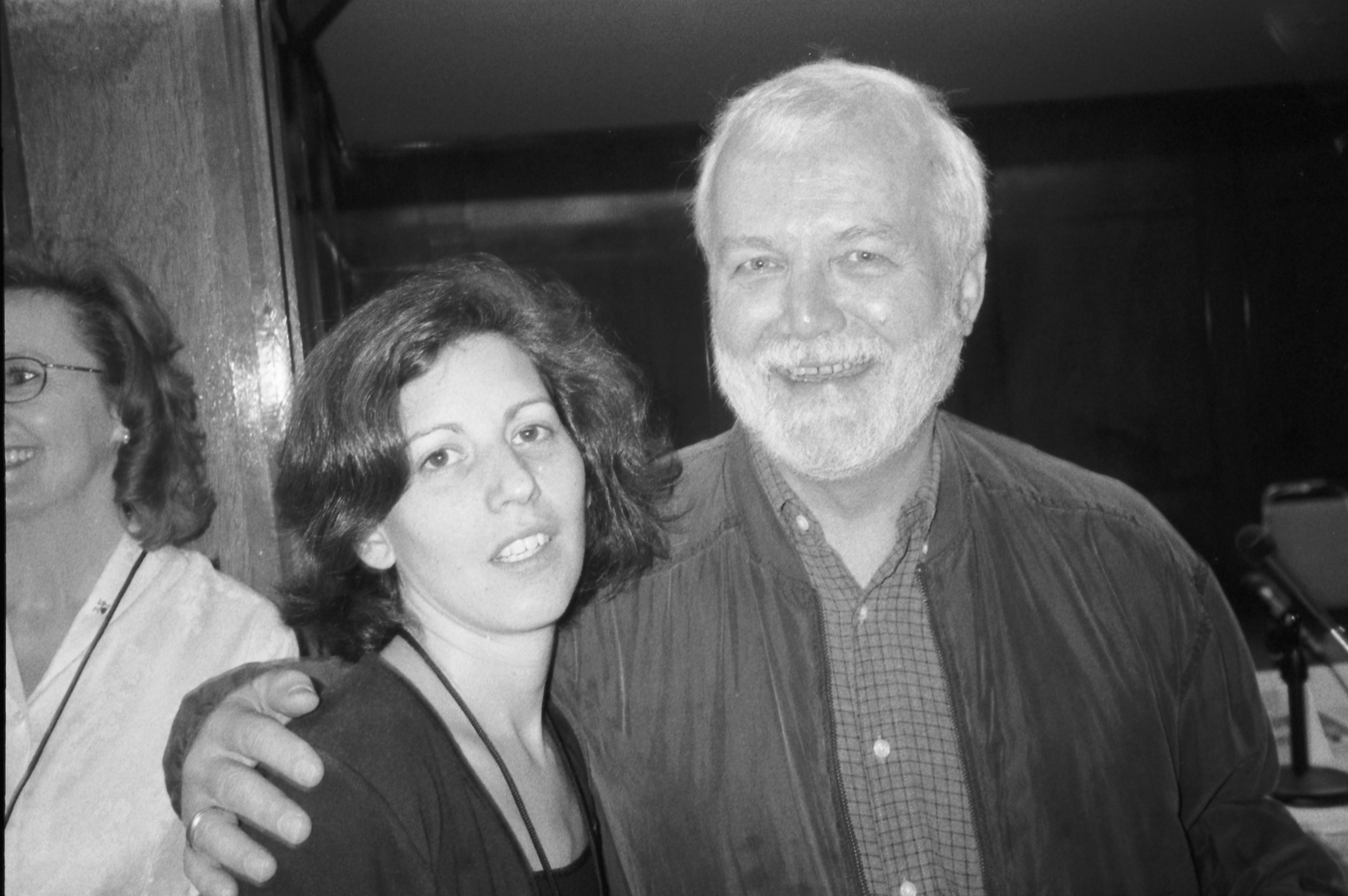

Chase Twichell, said “Russell Banks was the hardest working man she ever met.” In a Doc I saw after he passed. He spoke about what a monumental task it was to write “Cloud Splitter”, and that he put it aside from time to time and came back to it. My generation of photographers/multimedia artists tried to make it look effortless.

RB saw through me quickly when I asked him to write an introduction to “Adirondack Wilderness”. I showed him The multimedia piece that I had turned into that book.

He said, “I am usually resistant in being shown what to look at”. However he quickly let go and went with the flow of the 35 minute show until he emerged at the other side of the experience. I am grateful that he laid his gifted voice over my images.

GROUND : GO FIGURE

Nathan Farb’s Photographs

by Russell Banks

At first glance, but only at first glance, these are images of nature: Nature capitalized. And compared to those that follow, the image that opens the exhibit is essentially cartographic, a distant view of Mount Algonquin in the heart of the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York. It situates us in a scenically familiar spot on the rugged surface of the planet in a manner sufficiently conventional to let us momentarily get our bearings. It’s the locus for these photographs, their locale. It’s only a gate, however, and a deceptively familiar gate, that opens the way to the dizzying, Dantesque descent to come, Initiating a plunge into the earth, where we swiftly come to ground, chased there by physics (gravity, temperature, and light) and Nathan Farb’s furiously concentrated gaze. “The walking of man and of all animals,“ Emerson said, “is a falling forward.”

The images that open to us on the further side of that gate - enormous, sense-surrounding, dead-on visions of the earth- pull us through the surface of water, scree, lichen, rock walls, ice and snow, into the deep geological time and space, where ice is transformed into water, water into vapor, rocks are crumbled and devoured by plants, and trees give birth to boulders. Foreground switches place with background, and figure in the ground becomes the ground itself, and we recall that ground is the past tense of grind, that this particular noun is also emphatically a verb.

Though they reside in the singular concrete and portray the tangible, material world of rock, water, and plant life, the photographs are filled with the visual equivalent of linguistic leaps of allusion and reference. They overflow with double entendres, puns, and metaphors. Like poetry, the images first disorient and then reorient the viewer’s point of view. They change us- -when we stand before them, the pictures don’t move; we do. As in “Orebed Brook”, where one’s center of gravity shifts abruptly from a downward gaze on rock-face and icy water falling into a pool to a horizontal gaze, perpendicular to the floor we stand on, as if we have suddenly found ourselves standing inside an archeological dig looking at the successive floors of a series of ancient cities, or are driving in a car through a hill cut by a highway, speeding past layers of sedimented rock. In the passage of mere seconds, we watch falling leaves and sand particles drift in scrims for eons to the bottom of an ancient lake-bed where they settle and slowly begin to mineralize. Farb's drama, implicit in a single image, is tectonic in scale and has been measured microscopically. It’s as if his photographs provide us with x-ray vision, opening to our eyes the ground we stand not only on, but simultaneously in.

Typically, as in the photograph entitled “Scree”, the images swirl and re-configure themselves like the components of a dream. One thing is not like another; it is another. A pleat of old snow is the pelvis bone of a prehistoric horse. A boulder is a stone ax-head used for killing. A cold corner of the forest is the grave site of a bog-man, or it is the body of a Cro- Magnon hunter frozen to death in the Italian Alps, or the crumbling shawl of a fifteen-year-old Inca princess ceremonially interred atop an Andean peak. There is a continuous tension in these pictures between the literal and the figurative that corresponds to the ongoing exchange between figure and ground, between foreground and background, and it is dialectical, engaged, and therefore dramatic. In each photograph, there is a mysteriously evocative narrative that is comprehensive and, in so far as every part contributes to the overall effect, is Aristotelian.

It can be perilous to open oneself to this narrative: we depend for our emotional and intellectual equilibrium on keeping fixed relations between figure and ground, foreground and background, micro-cosmos and macro-cosmos, close-up views and aerial views. We want to be grounded. In the 14th century, however, the word ground, or grund, for Meister Eckhart, referred to the divine essence or center of the individual soul in which mystic union lies, where a spark resides which is consubstantial with the uncreated ground of the Deity. One might easily be led to speculate, given the evidence of the photographs, on the nature of Nathan Farb’s deity. So many of them are images of the female (not of the merely feminine): to Farb, the planet is moist, watery, filled with nutrients, constantly giving birth. “Bog with Pitcher Plants” is a primordial soup, and “Vernal Pond”, stilled and wholly abstract when viewed from a distance, comes to life when seen close-up: polliwogs and tadpoles school and swirl like spermatozoa. And from the evidence of “French Brook”, where light falls in pale bands and sunlit snow is inhabited by heat, the ground, or ground, evokes a deity for whom light and temperature are as substantial a firmament between the firmaments as the earthworks thrown up by the God of Genesis 1: 6-7 to divide the waters above from the waters below.

Are these religious pictures, then? Inescapably so. For they invite us to contemplate the whole of Creation, to meditate on the paradox of its irreducible complexity and infinite simplicity, even as we perceive both separately. Like prayer, these images sustain us by making us larger than the sum total of the minutes of our lives. At bottom, Nathan Farb’s relation to Nature (capitalized) is echt-American, which is to say, transcendental. It is Emersonian in intent and locale and is Buddhist in scale and mental methodology. “Echo Pond”, in which the dark branches of a tree fallen in water come forward against the reflected pale sky like the brush- strokes of a Zen calligrapher, might have been pictured in the mind of Thoreau, who, looking from the shore of Walden Pond, saw not his small corner of the universe, his private patch of ground, but the whole of it. “Show us the arc of the curve,” Emerson said, “and a good mathematician will find out the whole curve.” Farb has shown us the ground, and from it, like good mathematicians, we can figure the earth itself.

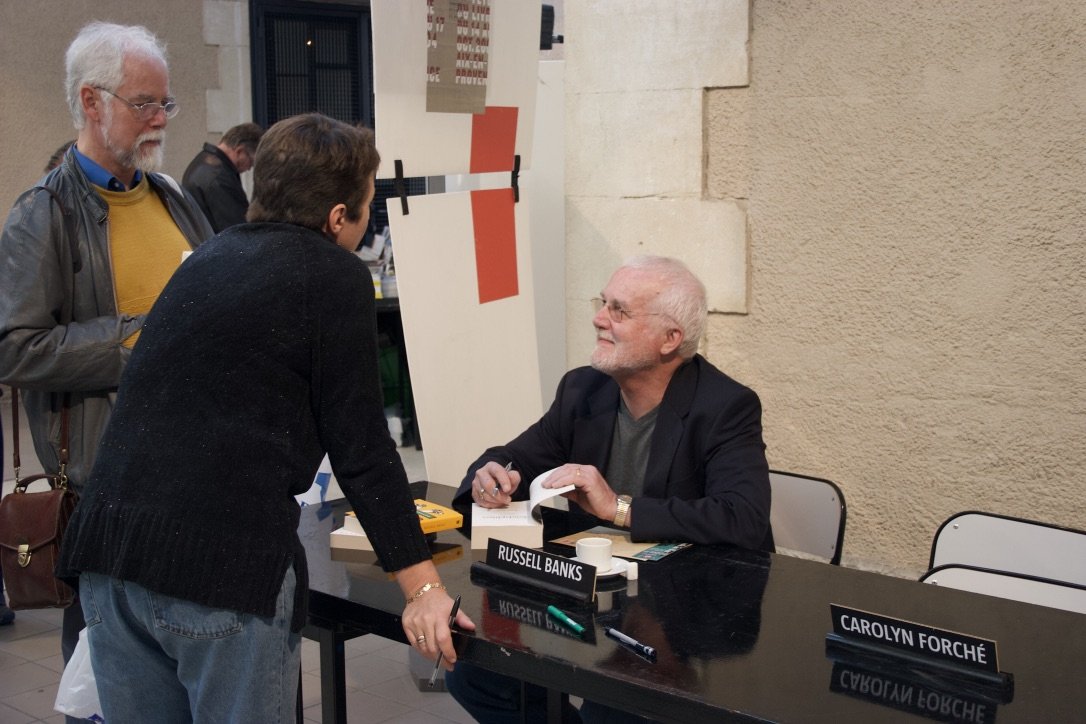

Cloudsplitter was written By Banks in the voice of one of John Brown's sons.

Russell did a reading of some paragraphs toward the end of this, his most ambitious and perhaps his greatest novel at the Willsboro, NY library on Dec 6, 2009. I got to there late and immediately turned on the camera while hiding behind a door. Here is six minutes of Russell's Cloudsplitter.